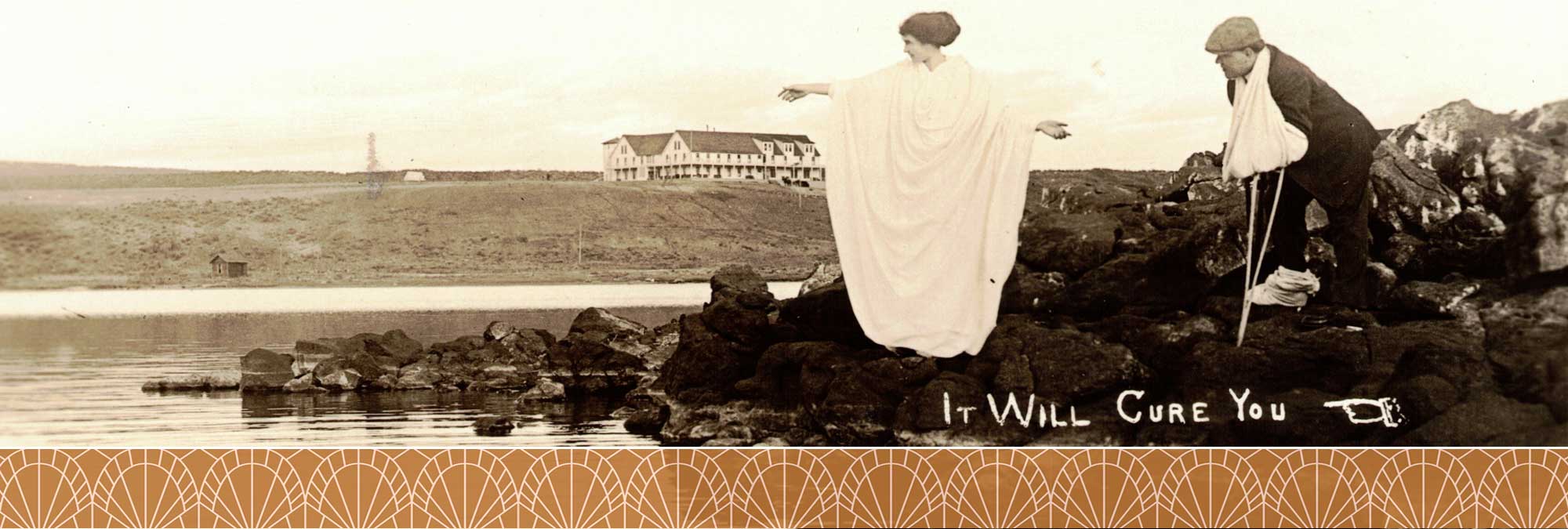

To behold my ancestor’s 19th-century handwritten manuscript was thrilling. And tucked inside the pages was an even bigger surprise.

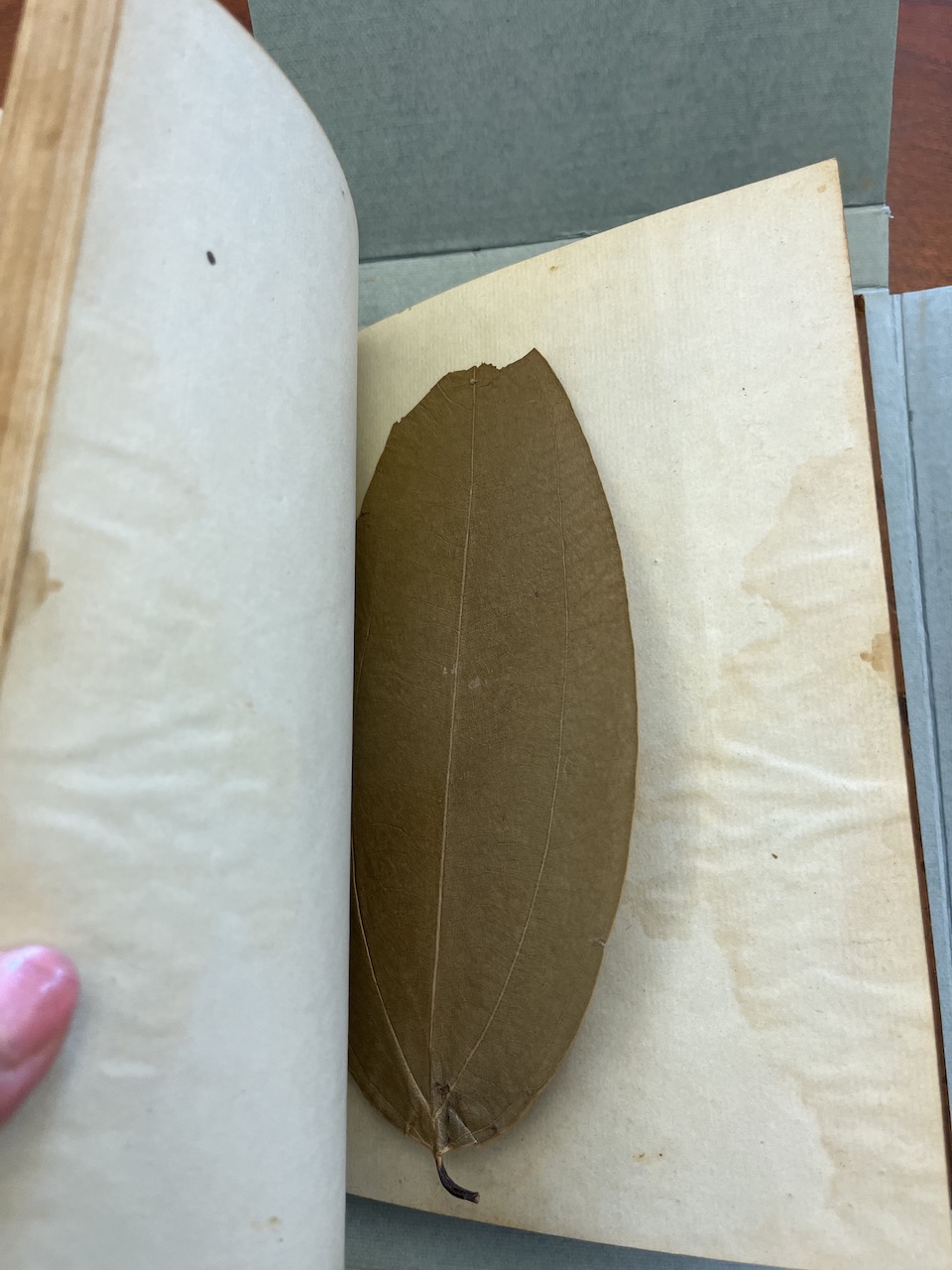

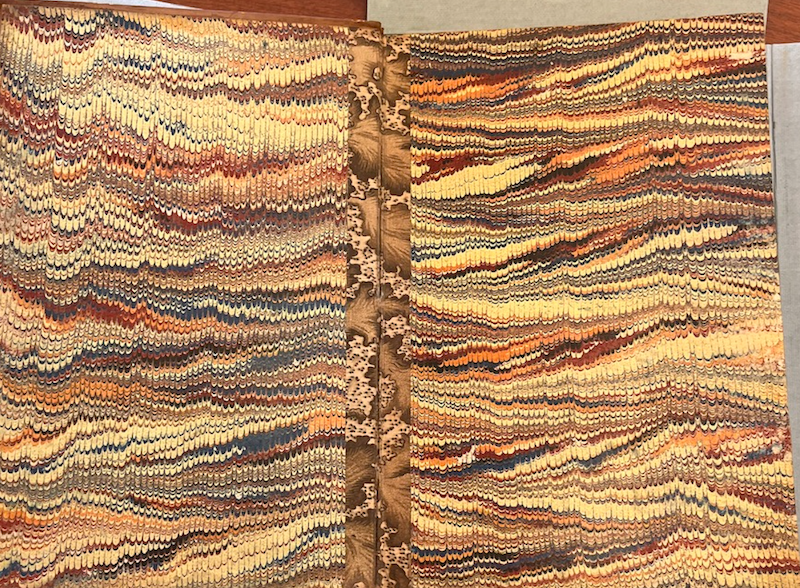

When I first happened upon the scuffed leather-bound volume in Princeton Theological Seminary’s Special Collections and Archives, I noticed that although the cover bore no title, it did have gorgeously marbled endpapers and heavyweight cotton bond pages. It was not an actual book, but rather a journal that contained the manuscript of a book.

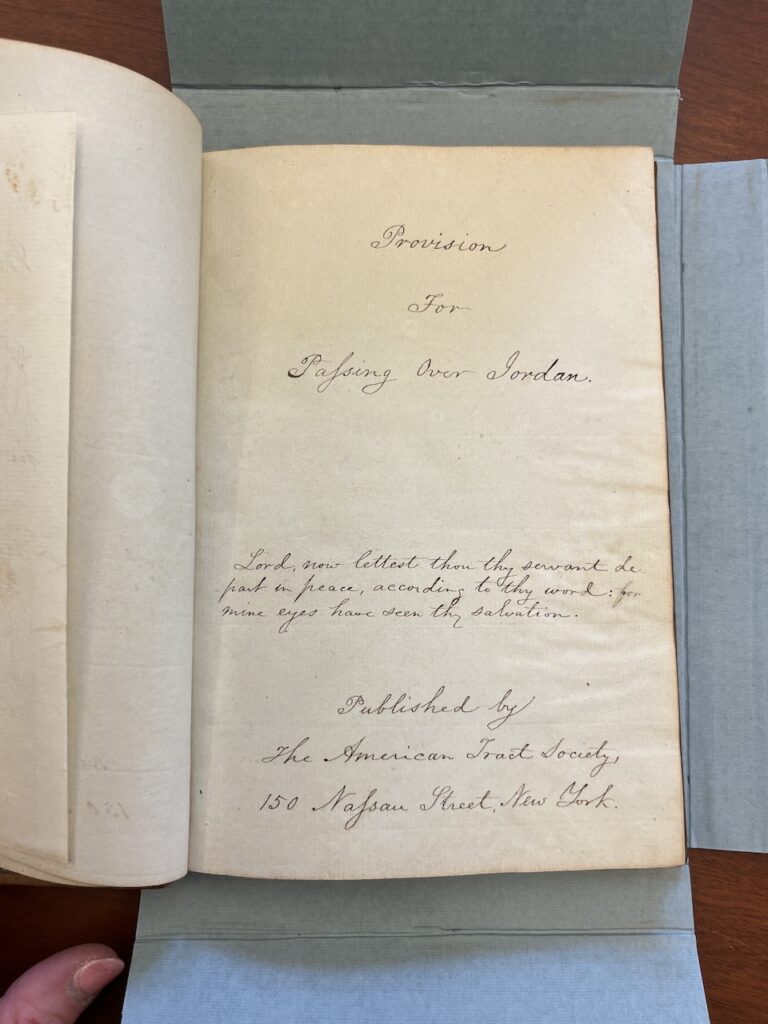

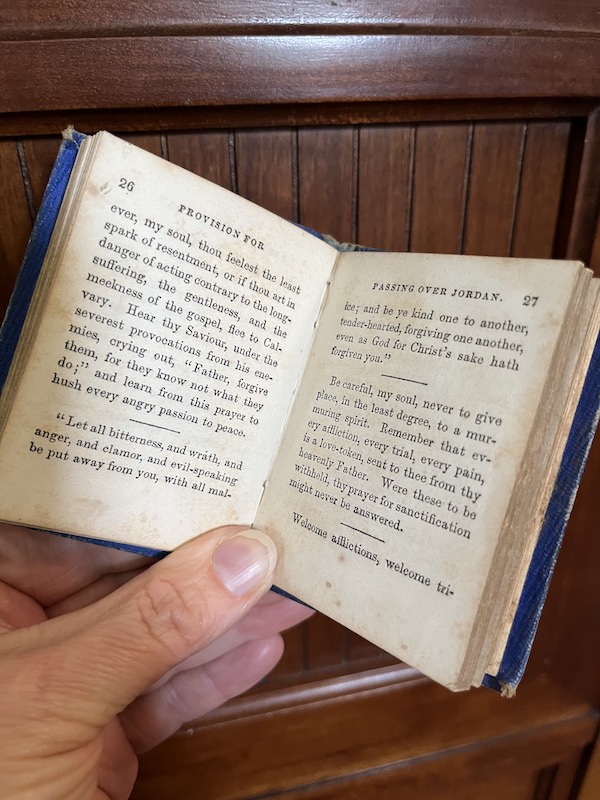

Inside there was an explanatory note written with a flourish (see right). The author was my great-great-great-great grandfather, the Rev. Dr. John Scudder (1793-1855), who sailed from New York City to India in 1819 as the very first American medical missionary. The American Tract Society published his Provision for Passing Over Jordan in 1846, the year that John returned to India after a four-year furlough in America to recover his health. As a miniature devotional, the book became a popular farewell gift pressed into the palms of travelers to wish them godspeed and give them something to ponder on the journey (and spend hours deciphering the tiny mouse-type.)

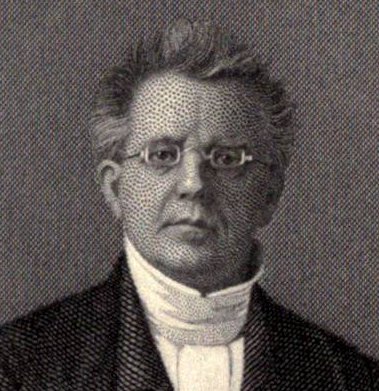

Dr. John Scudder.

with “f” for “s.”

This oversized version harkened back to an era when books were composed in longhand and then manually set in type, letter by painstaking letter. I assume that he took this copy to India to have the mission press reproduce it as a religious tract, which he distributed far and wide by the tens of thousands in his Quixotic quest to spread Christianity. Before me lay not only a connection to my family’s distant past but also the practical 19th-century version of backing up to the Cloud.

of

Passing Over Jordan

in the Handwriting of

The Author

The Rev. John Scudder M.D.“

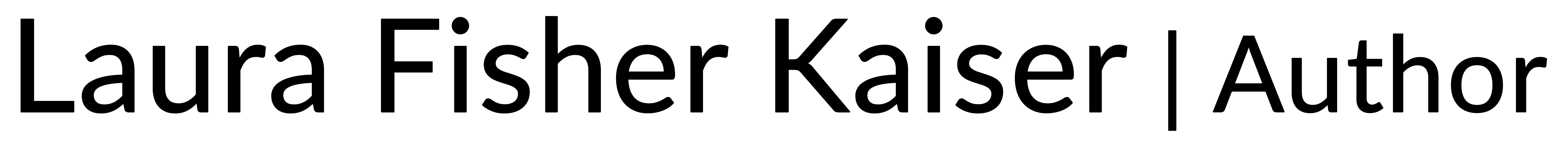

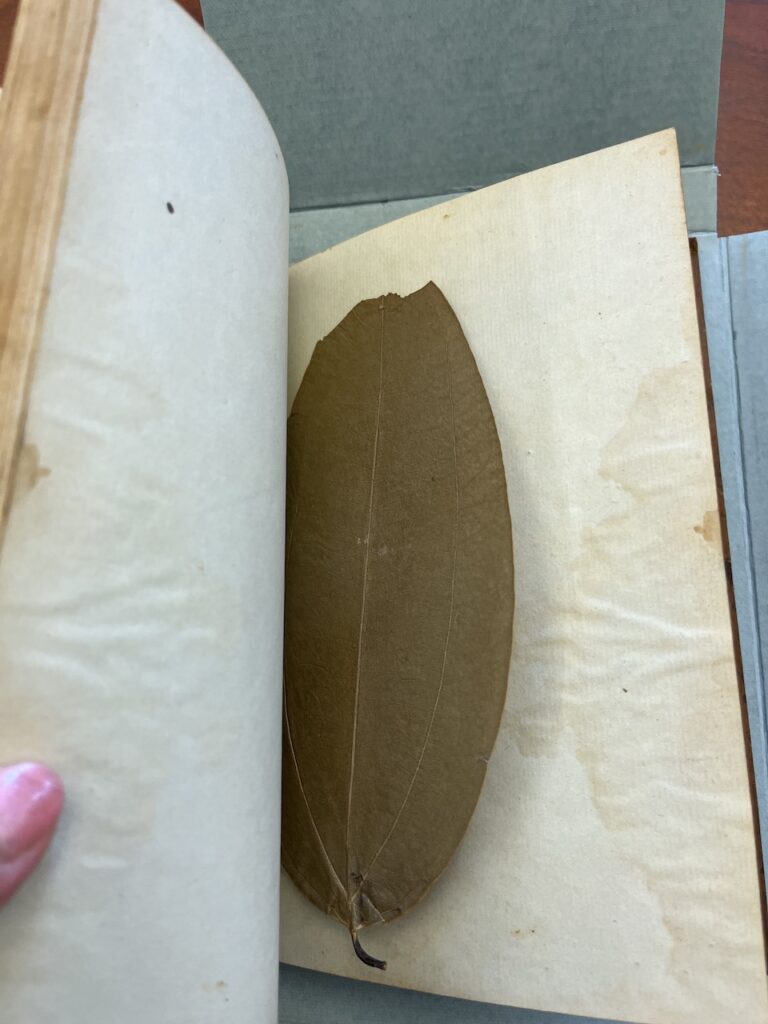

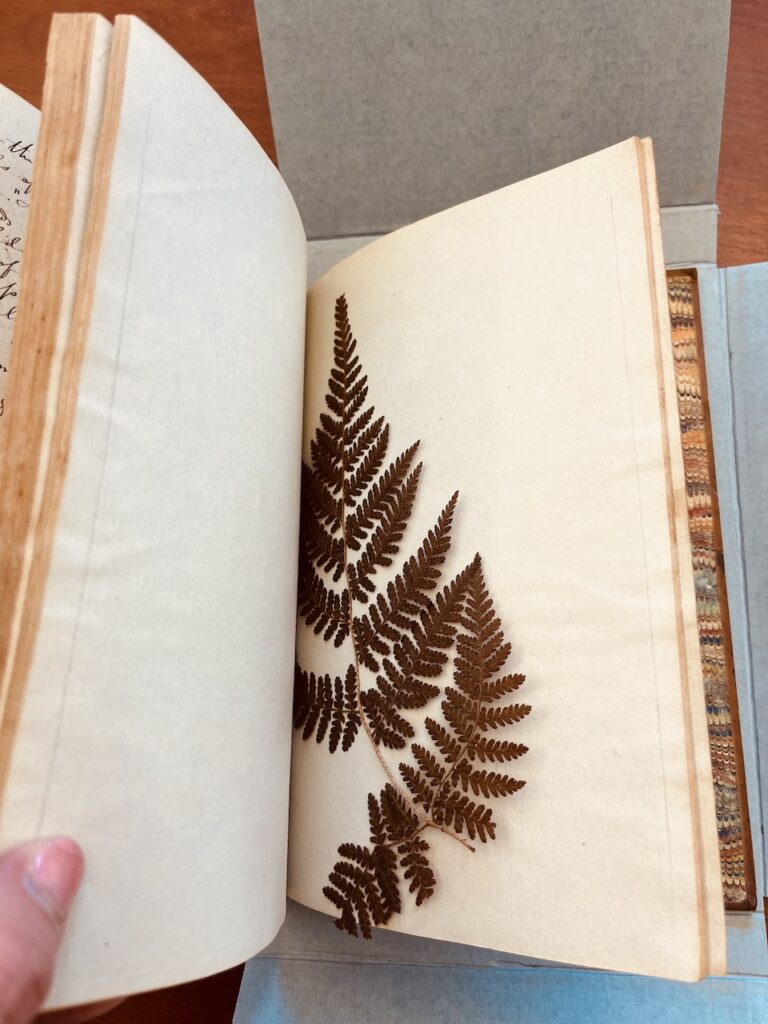

As I browsed the stiff volume, careful not to crack the spine, the pages fanned open to reveal two unusual bookmarks: a large ovate leaf with a khaki-green patina; and a fern, brown with age.

Was this John’s doing?

Quite possibly, yes. He was naturally curious and a naturalist by training. His preceptor at the (Columbia) College of Physicians and Surgeons had been the extraordinary Dr. David Hosack, who founded the nation’s first botanical garden on land that is now home to Rockefeller Center. When John first arrived in India, he had been mesmerized by the versatility of the palmyra palm and the ingenious ways the Tamils used every ounce of the tree for food, clothing, shelter, furniture, baskets, medicine, and, to his teetotaling disgust, potent toddy recipes.

Perhaps he plucked these leaves from up in the lush Nilgiri Mountains, where he went to escape the blazing heat of the plains. A friend of mine, who is both a master naturalist and a master gardener, thinks the ovate leaf might be cassia, also known as Indian cinnamon, based on its long vertical veins. That makes sense; John did wax poetic about the cinnamon-infused “spicy breeze” that greeted their ship as they neared the subcontinent, as promising a sign as the olive leaf in the mouth of the dove in the tale of Noah’s Ark. As for the fern, it looks to be a Nilgiri tree fern (Cyathea nilgirensis). And if John was not the one who preserved these botanical specimens, it could have been another family member–several dozen of whom followed in his missionary footsteps–caught up in the Victorian fad of Pteridomania.

I stared in wonder at these artifacts for several minutes, afraid that they would disintegrate into dust if I so much as breathed on them. Without thinking, I bent close to the page and inhaled deeply through my nose. I thought I detected the faintest of aromas, more bay leaf then cinnamon, something as old as the India ink dried on the page and as evocative as the idea of a long journey to the great beyond.